| Press the "Back" button on your web browser to return to the previous page. |

|

Not all Taichichuan instructors teach the same. There are differences in schools. There are also people who started to teach before having learned adequately. But differences do exist even among the best experts of the same school. Photographs of the early masters covered only key postures without showing the transitions. Accordingly, while the disciples can imitate fairly well the final postures, they may move differently in the transitions.

To do the exercise in its best tradition, it is necessary to compare the styles, understand the reasons and merits of each variation, and choose the best for your own purpose. This article illustrates the three major variations which were originated in the three earliest books on Taichichuan on the transition from the posture "high pat on horse" to "separate right foot".

A. The Pictorial Explanation of Taichichuan (1921) was written by Hsu Lung-hou, who learned from Yang Cheng-fu’s father, Yang Chien-hou. From high pat on horse when you have caught the opponent’s left hand, you retreat left foot toward left rear and pull your opponent’s left arm toward the same direction. Circle hands, form a cross, and at the same time retreat right foot beside left foot, toes down only. Separate the two hands and kick the right foot. This is the earliest transition ever recorded.

Although the series described is for the one-person exercise, this transition is best for self-defense purposes. When you retreat left foot to pull your opponent’s left arm toward your left rear, your opponent’s balance is impaired, yet you have perfect balance. When you retreat right foot and put down its toes in shifting full weight to the left leg, again you have perfect balance in kicking him. For self-defense, the movements can also be done at higher speed then variant C below. Stepping backward instead of to your left front for separating right foot toward your right front also has a greater impact in hitting your opponent.

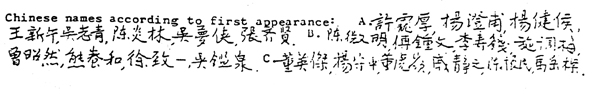

This transition was adopted by Wang Shin-wu (1941), Yearning K. Chen (English text 1947), Wu Chih-ching (1950), Wu Meng-hsia (1957), and Chang Chih-hsieh (1969).

B. The next book is Methods of Taichichuan (1925) by Chen Wei-ming, who learned from Yang Cheng-fu. It uses Yang’s photographs and is the first book on Yang Cheng-fu’s style. Chen Wei-ming’s full text of the transition is:

From high pat on horse, "when right palm is facing downward and left palm facing upward, with right hand above left hand, both hands follow the twisting of the waist to circle rightward, downward, and leftward. Following the waist and hand movement, step left foot toward northeast. Then circle up both hands from below to form a cross. Look at southeast, shift weight to left leg, raise right foot, toes down, and kick toward the southeast. The top of the foot should be flat. Simultaneously, separate two hands to both sides, right hand to southeast and left hand to northwest. Bend both wrists, fingers pointing up."

A detailed description of this transition was given by Yang Cheng-fu’s nephew, Fu Chung-wen in his Yang Style Taichichuan (1971). The movements are written in four steps.

1. From high pat on horse, partly twist waist and circle right hand rightward (clockwise). Gradually shift full weight to the right leg and raise left foot.

2. Step left foot to left front (northeast), heel down first. While gradually shifting body weight to left leg by stretching right leg and bending left leg, continue to slightly twist body rightward and circle back both hands toward your front.

3. Gradually shift full weight to left leg, twist body leftward, raise right foot, and form a cross with both hands.

4. Kick out right foot to right front (southeast). The leg is at hip level, the back of the foot is flat. Separate the two hands.

This transition is not self-defense oriented, but aimed at the smoothest movement in the one-person exercise. It is suitable even for the slowest pace, especially if your step is long. The twisting of waist and circling of the right hand rightward helps shift full body weight to right leg for lightly stepping the left foot to the left front.

You have continuous movement with uninterrupted energy. Accordingly, it is adopted in more books for the one-person exercise. These include: Yearning K. Chen (1943), Li Shou-chien (1944), Shi Tiao-mei (1959), Tseng Chiu-yien (1960), the Peking Government Physical Education Committee (1961), Shiung Yang-ho, (1963). The method is also used by Hsu Chi-I (1958) for the Wu Chien-chuan style.

C. In Application of Taichichuan, co-authored by Yang Cheng-fu and Tung Ying-chieh, (1931) is a third variation. From high pat on horse, if your opponent tries to use his right hand to catch your patting right hand, you pull his left arm to your left. Then sticking your left hand at his left wrist, step left foot to left front, sit on left leg, separate hands, and kick with back of right foot.

This is the self-defense interpretation of B. It is adopted by Yeung Shou-chung’s Application (1962). Although Yearning Chen used variation B is his one-person exercise, he used this to explain the self-defense implication in the same book. It is also used by Chi Ching-chih (1953).

In the very brief description of the one-person exercise in Tung Ying-chieh’s Taichichuan Explained (1948), he simply says, step left foot to left front, etc. Tung Hu-ling used this in his Application (1957). In Wu Chien-chuan style, it is used in the book co-authored by Chen Chen-min and Ma Yueh-liang (1935) and the one by Sophia Delza (1961).

This transition has the merit of simplicity in teaching. For self-defense, drawing your opponent to your left front when you start with your main weight at the rear leg is less effective than variant A when you draw your opponent to your left rear. The method also needs some technique to do it smoothly in the one-person exercise with continuous energy, especially if you want to do it really slow with long steps.

The choice of a transition may be based on self-defense needs. But each posture can be applied in several ways for self-defense. Unless you alter your transition between each two postures in each round of your daily exercise, you will not be able to include all the variations.

When application varies according to situation and to the action or response of your opponent, the best way is to practice the alternative techniques separately from your daily exercise for health.

In general, the one-person exercise is a compromise of self-defense and health needs. If your daily practice is to maximize the health benefits, you may study the different transition methods between each two postures and choose those which are the most consistent to your balanced, integrated, supple strength with uninterrupted energy and smooth, continuous movements. This is the way Yearning Chen wrote this particular transition in his Chinese book. To meet the double purpose of health and self-defense, postures and transitions should be designed so that minor modifications may adapt them to self-defense.

Practice for health is emphasized from the beginning of Taichichuan. In the Song of the Thirteen Motifs, there is a line, "contemplate the ultimate objective, prolong life, retard aging, and preserve spring."

Both Yang Cheng-fu and Wu Chien-chuan did their complete sets of Taichichuan in a little more than eight minutes around 1914. The slowing down of the same movements to about 20 minutes at present implies the continued shift of emphasis to health. This trend is relevant to the choice of transitions in the one-person exercise.