Lineage

Location

Pictures

Books/Videos

|

Home

Page Lineage Location Pictures Books/Videos |

|

At present, most of the Taichichuan taught claim to be of the Yang school, or its derivatives. But the styles vary considerably. There are many reasons for the variations, some of which have been indicated by Chen Wei-ming (T’AI CHI, November, 1982)[sic, actually 1981].

But one source is that Yang Cheng-fu’s own postures in his later years are not exactly the same as in his early years. While his students who followed him until his late years teach according to his latest postures, his students who learned with him only in his earlier years may teach according to his early postures.

In the preface to his book, "Taichichuan Exercise and Application," written in 1933, three years before his death, he said, "looking back into my photographs of a decade ago, I find that my present postures are much improved. This shows the unlimited scope of improvement in this art." The statement indicates his own preference of his later postures.

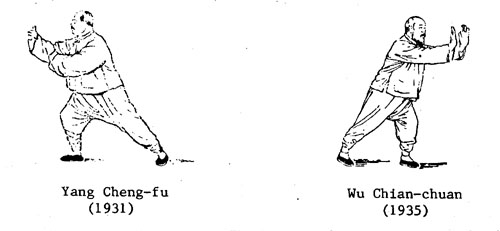

This short article can compare only one of his postures, namely, the "archery stance." In this stance, one stretches the rear leg and bends the front leg, with the trunk facing the front foot. The bent front leg is supposed to be the bow and the stretched rear leg, the arrow.

His early photographs were published in Chen Wei-ming’s "Methods of Taichichuan," Shanghai, 1925. From the preface, it is understood that these photographs were taken many years before publication. The fact that many of the drawings in Hsu Lung-hou’s book of 1921 were based on Yang’s photographs shows that they must have been taken some years before 1921.

In the archery stance, his rear foot points diagonally to his

side. In other words, when he stands facing west, with his right

foot at the front, he points his rear left foot toward the southwest,

about 45 degrees from the west-east line. His front foot is not

pointing directly to the front, but partly toward his left side,

say, about 10 or 20 degrees from the west-east line. The lateral

distance between the two heels (in this case, north-south) is

very wide. Some of the books written by his early students described

the two feet as being almost parallel to each other, like the

Chinese character "![]() ."

."

Yang’s latest photographs are published in the book co-authored by Yang Cheng-fu and Tung Ying-chieh, "Application of Taichichuan," Shanghai, 1931. In the archery stance, when he faces west, most of his rear foot forms about an 80 degree angle with the west-east line. Each photograph being separately posed in a studio, his foot angle is not always the same, even for the consecutive movements of the same posture. Some are 90 degrees or even slightly more than 90 degrees. The front foot is not in an angle, but points directly to the front. The lateral width between the two heels is narrower than that in his earlier photographs.

Either his early or later postures serve the particular purpose of Taichichuan. This self-defense art emphasizes yielding and neutralization of one’s opponent’s force. In either of his postures, he can bend his rear knee over his rear toes to twist his hips and waist partly sidewise and shift his torso rearward.

In attacking forward, he can use the stretching strength from his rear leg to twist his hips and waist to face the front, propel his body forward, and use the bowed front leg as a brake to prevent him from falling forward.

Thus, Chen Wei-ming, who learned from Yang for seven years in his early days, taught according to his early style. Tung Ying-chieh, who learned with Yang for more than 15 years and was with him until his late years, learned both Yang’s early and later styles and taught according to his later style.

The mixing of the two styles may not always produce the same desired effect. For example, if you maintain the foot angle of Yang’s early photographs but with shorter lateral width between the two heels like his later photographs, you will feel your rear knee hurting when you yield by bending your rear leg, and cannot shift your torso sufficiently rearward. With a shorter lateral width between the two heels and at the same time the front toes turned partly sidewise toward the rear toes, you will find that you cannot turn your hips and point your tailbone to face your direct front for an effective forward attack. This illustrates one of the reasons for not indiscriminately mixing styles.

A characteristic of Yang’s both early and later postures is that his foot steps are very long, and those in his early years look even longer than in his later years. But even the steps in his late years are still much longer than most of the Yang styles currently taught in the United States. When Taichichuan became increasingly popular in China since the 1940’s (after Yang’s death) among the middle-aged and old people, it is reasonable to expect the gradual shortening of steps with a higher stance by these people. In the United States, where the majority of people learning Taichichuan are in their 20’s and 30’s, however, a longer foot step should give them the proper exercise.

An attempt by the students of the Yang style to imitate his foot steps when he was 50 years old should not be considered all that demanding. His student Chen Wei-ming, who published Yang’s first set of photographs, was older than Yang, and still used the very long steps like Yang’s early photographs. When trained in long foot stance, one can easily change to short stance. But the reverse is not true. Other advantages of practicing with long foot stance have been given in our translation, "Chen Wei-ming on Foot Stance," T’AI CHI, September, 1981.

There is another point common among Yang’s early and later photographs. In his archery stance, when his front leg is bent forward, his trunk, from the rear foot through the calf, thigh, tailbone, and the back to the shoulders, form a forward, inclining straight line about 60 degrees with the ground, with the tailbone at the middle. This allows full transmission of strength from the rear leg to the forearms without a break in between, so that the supple strength is fully integrated. Wu Chian-chuan (1870-1942), founder of the Wu style, which is only second in popularity to the Yang style, also has his rear leg joining his trunk to form a forward inclined straight line, from his rear heel to his shoulders, with the tailbone at the center of the line. Therefore, both the most influential styles use this leg-trunk relation in the archery stance. From the drawing of Wu, below, one may also see the feet angles of Yang Cheng-fu in his early years.

The forward postures assumed by Yang Cheng-fu and Wu Chian-chuan conform to Chen Shin’s statement that the rear leg gives the pushing strength and the front leg gives the braking strength. Chen (1849-1929), the theoretician of the Chen style, called this form as relatively firm at the rear and relatively light at the front. This posture also confirms the Chen Wei-ming statement that "one leg is bent and one leg is straight," as well as the Tung Ying-chieh statement that the rear leg is more firm than the front leg because strength starts from the rear heel.

The next issue of T’AI CHI will carry an article on some recent variants of the Yang style.

Note on drawings: The drawing of Yang Cheng-fu is taken from the book by Fu Chung-wen, "Yang Style Taichichuan," 1963. The drawings in the book are mainly based on the photographs in the book by Yang Cheng-fu and Tung Ying-chieh, "Applications of Taichichuan," 1931. However, the artist deliberately modified some of the drawings to make Yang’s rear foot angle closer to Yang’s early style, and has inserted other drawings showing the transitions without the basis of Yang’s photographs. A number of books published in Taiwan, Japan, and the USA reproduced such drawings without pointing out these facts. The drawing of Wu Chien-chuan is taken from Hsu Chieh-I, "Wu Style Taichichuan," 1958. Those drawings are based on Wu’s photographs which were first published in Wu Kung-chao’s "Essence of Wu Family Taichichuan," 1935.

Mr. Wu teaches in Palo Alto, CA.