Lineage

Location

Pictures

Books/Videos

|

Home

Page Lineage Location Pictures Books/Videos |

|

The most popular style of Taijiquan today is that of Yang Chengfu, plus the many modifications of his methods. Each of these variations is different in the external forms and the spirit because the developed of each variation had incorporated his own personality, individual understanding, and insight into the art. Once source of such diversities was Yang Chengfu himself who continuously made modifications in order to improve his art.

The Chen style Taijiquan has evolved for 300 years and 11 generations from Chen Wanting to Chen Xiaowang at present. There are also brothers and cousins of the Chen family who contributed their talents to improve the art. In contrast, after departing from the Chen style, the Yang style had gone through only three generations to Yang Chengfu in about one hundred years. It was during the last ten years of Yang Chengfu's life that he made the most important improvements. Unfortunately, many of his students did not recognize his changes and a few even considered some of Yang’s improvements as deterioration.

When each of Yang’s direct students insisted upon teaching only in the way each had personally learned the art and with scant or no attention to Yang’s later improvements, they create even more confusion. It even gives an impression to Yang’s third and fourth generation disciples that there are no rules in Taijiquan. This encourages each author to design a Taijiquan series of his own, with different forms and different principles. This practice is prevalent in the United States where there are more derivatives of Yang style than in China. This article attempts to explain some of Yang’s obvious improvements as can be observed from his external forms. It also presents the reasons justifying his own changes will also help identify those changes made not by the Yang family, but by other teachers.

The first set of Yang Chengfu’s photographs was published in Chen Weiming’s book, "Methods of Taijiquan," 1925. The second set was published by Yang Chengfu and Tung Yingchieh in a book called "Application of Taijiquan," 1931. Yang posed for the photographs and Tung wrote the text of the book. Subsequent changes were not formally described in any literature after these publications. There were also no attempts by other authors to compare the differences that can be found in the two sets of Yang’s photographs. It is worth pointing out that Yang’s book of 1934, "Taijiquan for the Body and Application," continued to use his photographs that were published in 1931. In this article, we will examine in detail some of Yang’s changes based on these two sets of photographs. Unfortunately, photographs of the post-war reproductions of pre-war books are not clear enough for copying, and hand traced pictures of Yang often have his rear foot angles reduced.

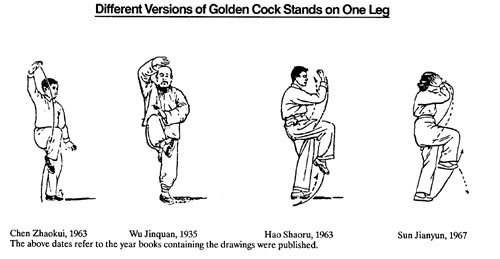

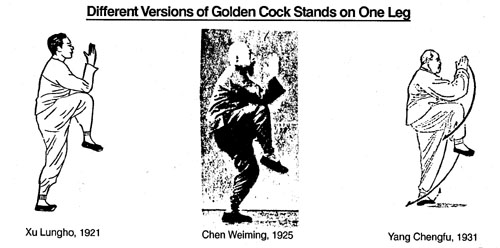

(1) Golden Cock Stands on One Leg — A misinterpretation sensationalized.

The only author who has pointed out changes in a few of Yang’s external forms was Zeng Zhaoran (alias Tseng Ju-Pai) in his "Complete Book of Taijiquan," Hong Kong, 1960. A misinterpretation that attracted popular attention was in the posture, "Golden Cock Stands on One Leg". Zeng said that when Yang performed this posture in his early years, his elbow would touch the knee. In later years, as Yang gained significant weight, he could no longer touch his knee with the elbow because his stomach was so large that it would be too strenuous to raise his knee significantly (p. 115).

Because of this belief, Zeng deliberately used Yang’s 1925 photographs for depicting the posture, "Golden Cock Stands on One Leg," in his 1960 book although most of Yang’s 1931 photographs were used in the same book.

Zeng’s strong position had significant influence over many readers. Lu Cheng published an article in the periodical, "Bulletin of Taijiquan Research," Taipei (No. 39, 1970) fully supporting Zeng’s opinion. Then in 1980, Jou Tsung Hwa also emphasized in his English book, "The Tao of Tai Chi Chuan," that Yang’s early photographs for "Golden Cock Stands on One Leg" had the elbow touching the knee but was then unable to do so in the later years due to Yang’s immense stomach. In 1984, John Reider quoted Jou’s statement and endorsed it in the "Inside King-Fu" magazine. At least four authors believed Zeng Zhaoran’s speculation, and it was mentioned in a Chinese book, a Chinese periodical, an English book, and an English periodical from 1960 to 1984. No one has yet challenged this assertion.

We have examined all the books about this posture. Those representing the other four major styles — Chen, Wu, Sun, and Hao — did not touch the knee with the elbow. Wu Mengxia of the Yang style, whose teacher was a student of an elder brother of Yang Chengfu’s father, also did not touch the knee with his elbow. As far as the author knows, books that used photographs showing the elbows touching the knee include only those by Xu Longhou, Yang Chengfu, Chen Weiming and Li Shouquan. Xu Longhou learned the art from Yang Chengfu’s father Yang Jianhou. Chen Weiming learned from Yang Chengfu, and Li Shouqian learned from Yang Jianhou’s elder son, Yang Shaohou. We could deduce that the posture in which the elbow touched the knee was started by Yang Chengfu’s father, Yang Jianhou. Yang Chengfu’s later revision was just a return to the tradition of his earlier ancestors.

We do not see the merits of connecting the elbow to the knee. The author had asked a whole class of new students to experiment with both variations before they learned this posture. Most new students claimed that touching the knee with the elbow made it easier to stand firm. The advanced students however, said that touching the knee with the elbow made it difficult to straighten the trunk of the body and had the tendency to compress the spine. In Chen Weiming’s photograph, his trunk leaned forward. The students also said that if the upper arm and the thigh were parallel to the ground, knee and elbow not touching, the stance would become more firm and comfortable and would extend the spine upward.

Based on Yang Chengfu’s book, "Application of Taijiquan," 1931, the hand in the Golden Cock posture is to lift an opponent’s upper arm while the raised knee attacks the abdomen. Alternatively, while raising the opponent’s arm with a hand, one can bend at the raised knee and use the toes to kick the shin. Thus the hand and the foot attack different parts of the opponent’s body simultaneously. If the elbow were to touch the knee, the usage of the hand and the knee will not be as flexible. We must admit that Yang’s later modification to this posture was a great improvement. Based on Yang’s 1931 photographs, his stomach was not large enough to hamper touching the knee with his elbow. So the change in the external form was deliberate and not a result of his physical shortcoming.

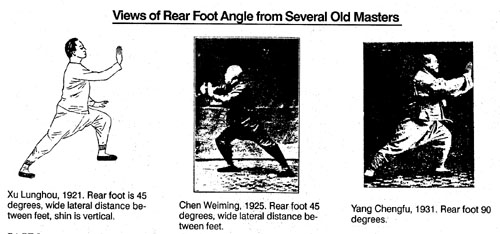

(2) Rear Foot Angle — An important contribution generally ignored.

The specific positions of the foot and hand in the external forms in a posture are not the most important. Instead, one should attend to the whole body alignment, strength application, and the spirit.

In Yang’s 1925 photographs with bow stance, his rear foot pointed at about 45 degrees sidewise. In his 1931 photographs, this rear foot was at about 80 degrees sidewise. The published 1931 photographs generally showed somewhere between 70 and 90 degrees. It may be noted that Fu Zhongwan used pen-traced drawings based on Yang Chengfu’s 1931 photographs in his 1963 book. but the author had reduced Yang’s rear foot angle in a number of the photographs.

In Taijiquan, strength is rooted at the rear foot for transmission through the trunk to the arms. In a forward bow stance with a long footstep, if the rear toes point at an 80-degree sidewise angle, the forward strength starts from the rear heel and can be very powerful. If the rear foot forms a 45-degree angle sidewise, unless the footstep is very short, the forward strength from the rear leg can only start from the inner edge of the rear foot behind the large toe instead of from the heel. The longer the footstep, the weaker the strength. An 80-degree rear foot angle thus allows the application of optimum forward strength.

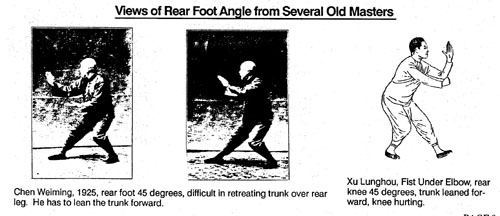

The rear foot angle also seriously affects the retreating of the trunk over the rear leg. In Yang Chengfu’s 1931 photographs for "divert and draw" (or "pull back"), his rear foot was about 90 degrees sidewise, rear knee over rear toes also 90 degrees sidewise. The trunk was perpendicular to the ground and the whole body sat comfortably on the rear leg. There were no photographs of his for the same posture in 1925. Chen Weiming’s photographs for this posture in the same book used the 45-degree rear foot angle. His rear knee was bent 45 degrees sidewise and was much more forward than his rear toes (See illustration #4). Thus his upper body could not vertically situate itself over the rear leg without hurting his knee, forcing him to lean the trunk forward into an uncomfortable position.

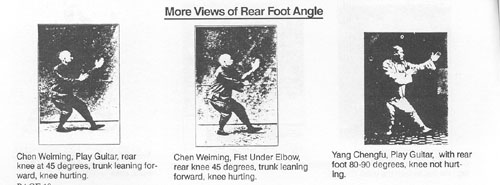

For the postures "Play the

Guitar" and "Hammer under Elbow", Yang’s 1931

photographs showed the 80-degree rear foot stance, the whole body

looked natural and comfortable. In Chen Weiming’s 1925 pictures,

because his rear toes pointed 45 degrees sidewise, he had to also

bend his rear knee 45 degrees sidewise. The trunk seemed unable

to sit back over the rear leg and was leaning forward. The front

leg had to support significant body weight, making it difficult

to lightly raise the front foot to advance or retreat.

For the postures "Play the

Guitar" and "Hammer under Elbow", Yang’s 1931

photographs showed the 80-degree rear foot stance, the whole body

looked natural and comfortable. In Chen Weiming’s 1925 pictures,

because his rear toes pointed 45 degrees sidewise, he had to also

bend his rear knee 45 degrees sidewise. The trunk seemed unable

to sit back over the rear leg and was leaning forward. The front

leg had to support significant body weight, making it difficult

to lightly raise the front foot to advance or retreat.

Wu Jianquan’s rear foot was parallel with his front foot. But he used a shorter step and a higher stance. he also raised his front toes and balls of the foot when the trunk was shifted over the rear leg thus removing any unnatural pressure on the rear knee. Yang Chengfu used a longer step and a lower stance and he did not raise the front toes and balls of the foot when retreating his trunk over the rear leg. His solution in the 1930’s was to increase the angle of the rear foot to about 80 degrees, thus allowing the trunk to shift back over the rear leg. It was an important improvement.

While the Wu style and Yang style were both derived from Yang Chengfu’s grandfather, Yang Luchuan, each style solved their common problems with different methods. The result is their separation into two distinct systems, with different emphasis in all aspects, especially in the method of strength application.

To allow the free flow of internal energy through the whole body, Taijiquan emphasizes the rounding of the thighs and the arms and moving the feet and hands in circular paths. With a little experimentation, any person can find out that one can round the thighs much better with a rear foot angle of 80 degrees sidewise than at 45 degrees. The rounding of the thighs with a 80-degree rear foot angle is demonstrated in Tung Huling’s photographs in "T’AI CHI", February, 1993.

In Zeng Zhaoran’s "Complete Book of Taijiquan," Hong Kong, 1960, he used Yang Chengfu’s 1931 photographs with the rear foot pointing at about 80 degrees sidewise. In the text however, he explained that the two feet should be parallel. He even included a diagram illustrating the parallel feet form — both front foot and rear foot pointing 45 degrees sidewise. Then in Fu Chungwan’s book, "Yang Style Taijiquan," Beijing, 1965, the author used drawings traced from Yang Chengfu’s 1931 photographs with the rear foot pointing about 80 degrees sidewise. But he explained in the text that the two feet should be parallel and had a diagram showing the parallel feet form. In both cases, it appeared that the authors were not aware of the fact that their foot-position diagrams contradicted those in Yang’s pictures in the same book.

It is unknown why people favor the 45-degree rear foot angle. Even after Yang published his latest forms in 1931, many Taijiquan books published after the second world war, supposedly based on the Yang style, included in the instructions that the rear foot points 45 degrees sideways and the front foot points directly forward.

Tung Yingchieh studied with Yang and served as Yang’s teaching assistant for a total of twenty years. He also traveled with Yang to different provinces and wrote the text of the book "Application of Taijiquan" for Yang that was published in 1931. In Tung’s own 1948 book, "Taijiquan Explained," his rear foot was at 70 to 80 degrees sidewise. When he shifted his trunk rearward, his rear knee bent sideways in the same angle as the foot and his trunk was over his rear leg. This was based on Yang’s latest teaching. Tung’s son Tung Huling also did the same. Li Yaxian also studied with Yang for about ten years. All his bow stance photographs showed the rear foot to be at a 80-90 degree angle.

The improved rear foot angle was Yang Chengfu’s own innovation and an important factor in raising his mastery of Taijiquan to a new height. Despite such an important contribution to Taijiquan, there has not been any published literature pointing out his change. In fact, many of his students who claimed to have learned directly from him in the 1930’s, after the publication of his 1931 book, continued to use the 45-degree rear foot angle. One of the reasons was that after Yang had moved from Beijing to central and south China in 1928, there were many teaching invitations that took Yang to various places. Since he was traveling so much, most of his students in the 1930’s were actually taught on his behalf by his senior students who were called "senior brothers" by the new students. Each senior brother would teach differently depending on when each studied with Yang. Only the few senior students who were closest to Yang and had spent a long time with Yang could automatically follow all of Yang’s changes with confidence. New students who learned from several senior brothers might choose to follow the teaching of the most senior brother. For example, Zeng Zhaoran learned from Chen Weiming in 1933 but appeared to have not recognized the new 80-degree foot angle of Yeung Sauchung, even though Yeung was assigned by Yang to tutor Zeng in 1935 and 1936. Zeng insisted in the text of his 1960 book on using the 45-degree rear foot angle taught to him by Chen Weiming.

(3) Lateral Distance Between the Feet.

The rear foot position of the Yang style continued to be at 45-degree sidewise up into the 1920’s. In this position, it was very difficult to fully shift the trunk over the rear leg. To achieve a fully retreated form, early members of the Yang family had widened the lateral distance between the feet. This was shown in the 1921 book of Xu Longhou, who learned from Yang Chengfu’s father, and also shown in Yang’s photographs in Chen Weiming’s book of 1925. In a wide and long foot stance, even though the rear foot is 45 degrees sidewise, it is still possible to bend the rear knee and retreat the trunk over the rear leg without excessive strain on the rear knee as long as the trunk retreats diagonally and not directly rearward. For instance, let's suppose the body is facing West and the left foot is 45 degrees with the West-East line. When retreating with a wide lateral foot distance, the body would shift partly towards the Southeast instead of due East. The rear knee could then bend over the rear toes without feeling strained. when advancing toward the West, the body would not advance due West but partially toward Northwest. Relative to the line of forward and rearward movement, the "effective rear foot" angle was more like 60 degrees instead of 45 degrees. When Yang Chengfu used an 80-degree sidewise rear foot in the 1930’s, he could reduce the lateral distance between the two heels to about shoulder width without the comprise of a wide lateral foot distance.

(4) The Parallel Feet.

In the earlier years, while widening the lateral distance between the feet did solve the problem of retreating the trunk over the rear leg without hurting the knee, it created a new problem. In applying forward strength, this strength could not be directed exactly forward but partially sideways toward the direction of the front foot. The wider the lateral distance, the larger this sidewise tendency. The solution in those years was to point the front toes partially inward looking as if the two feet were in parallel. This allowed the front foot to also apply a partially sideways braking strength to keep the balance. Although Yeung (Yang) Sauchung taught Zeng Zhaoran in 1935 the 80-degree rear foot angle, Zeng included a diagram in his book that showed both feet pointing 45 degrees sideways and in parallel. He must have learned this from his senior elder brother Chen Weiming.

From most of the 1925 photographs of Yang Chengfu and Chen Weiming., however, the inward pointing characteristic of the front foot was not obvious. Only among a few photographs of Xu, Yang, and Chen did we see something resembling the parallel feet form. It could be that the parallel feet form was a concept passed down in the Yang family. It might have been a mental note to emphasize the use of the slightly inward pointing front foot to counter the sidewise momentum. For instance, when the stance was wide, directing the braking strength at the inside edge of the front foot would enhance the diagonal braking effect.

All the complicated problems were solved by Yang Chengfu’s modifications in his 1931 book. With a lateral heel distance of shoulders’ width and a rear foot angle of 80 degrees, one can apply the maximum forward strength directly from the rear heel rather than from the side of a 45-degree rear foot. This makes it possible to direct the full forward strength towards the front with very little sidewise wastage. While the narrower lateral foot distance allows the front foot to point straight forward, the perpendicular shin allows one to apply the braking strength at the front leg during frontal issuance of strength. By using the 80-degree rear foot angle to ease shifting of the trunk over the rear leg, all the benefits were realized. It is the simultaneous changes in all these directions that advanced Yang Chengfu's art of Taijiquan to a higher level.

(5) Creation of New Styles.

To summarize, a rear foot angle of 45 degrees sidewise does not allow the application of full forward strength from the rear heel, especially if the footstep is long. It will also hurt the rear knee when shifting the trunk rearward, especially if the stance is as low as Yang Chengfu’s. The original solution by the Yang family up to the 1920’s was to have a wider lateral distance between the heels, so that the "effective" rear foot angle along the diagonal line is more than 45 degrees. To offset the sidewise diversion of forward strength, they angle the front foot partly inward making it look as if the two feet are parallel. All these factors combined to address problems in the old system.

Yang Chengfu solved the ancient problems of the 1920’s by simultaneously introducing two measures: (1) widen the rear foot angle to 80 degrees; and (2) narrow down the lateral distance between the heels to shoulder width with the front toes pointing straight forward.

Practically all of Yang’s disciples at present have adopted the narrower lateral distance between the two heels introduced in the new system, but many still use the 45-degree rear foot angle of the old system. This hybrid foot alignment destroyed the traditional offsetting measures of the old Yang style so that all the original problems reappeared. The 45-degree rear foot angle of the old system. This hybrid foot alignment destroyed the traditional offsetting measures of the old Yang style so that all the original problems reappeared. The 45-degree rear foot angle generates strength from the side of the foot instead of from the heel, thus weakening the forward strength. There is more pain in the rear knee than Chen Weiming had experienced when the trunk is shifted rearward, since the hybrid system with a narrower lateral foot distance no longer has room for a diagonal retreat.

To solve these two recurring problems caused by the hybrid foot alignment, most contemporary instructors teach their students to use a short and high foot stance. The shorter stance allows the application of short uplifting strength from the whole rear foot instead of long forward strength from the side of the 45-degree rear foot. the high stance reduces the pain in the rear knee when shifting the trunk rearward.

With this foot formula and the short and high stance, however, many of the methods of doing the traditional Yang style have to be altered. These are especially so in the various ways of applying the integrated strength. The combination of a 45-degree rear foot angle with short and high stance also does not allow the rounding of the thighs. With the change in the methods of strength application, many other aspects of doing the exercise must also be revised accordingly. The result is the creation of certain new styles very different from all the five major styles established before the second world war, namely, the Chen, Yang, Wu, Hao, and Sun styles. This situation is especially prevalent in the United States. These styles are not the concern of this article.

(6) Front Knee Alignment.

In the "Talk on Practicing Taijiquan," narrated by Yang Chengfu and recorded by Chang Hungkui, it said, "the leg should only bend until the shin is perpendicular to the ground. To exceed this position constitutes over-application of strength. The body will thus rush forward and lose its balance." What he meant was the front shin. This view is consistent with the principles of the Chen Family Taijiquan which does not use the forward bow stance. Hung Junsheng of the Chen style wrote in his "Three Worded Bible" that the two knees are to line up with the heels. In a footnote, he added, "a knee may not be in line with the toes, or the shin will slant forward resulting in double-heaviness, thus rendering all movements sluggish". (See "Chen Family Taijiquan Research," Vol. 3, p. 7). When the knee lines up with the heel, the shin is perpendicular to the ground.

In Yang’s 1925 photographs, his front shin was generally perpendicular to the ground. There were cases where the front shin slanted forward. Sometimes, the front knee was behind the toes, sometimes over the toes. In most of his 1931 photos, the front shin remained perpendicular. This was an improvement that requires better restraint of the forward strength. At present, there are still many books that claim to be of the Yang style and yet explicitly teach the knee lining up with the toes. Among all the Taijiquan authors, Li Yaxian, who was with Yang for 10 years, seemed to be the most outspoken in objecting to positioning the front knee on top of the toes. Tung Yingchieh’s front knee also never reached his front toes.

Yang’s "Talk on Practicing Taijiquan," being a record of a lecture, was neither included in Chen Weiming’s 1925 book nor in Yang’s 1931 and 1934 books. It was only reproduced in Shi Diaomei’s book of 1959 and Fu Zhongwan’s book of 1963. It is possible that the lecture presented after 1931 was known to only a few people before the second world war; so not many authors noticed. As a matter of fact, many of the photographs of Xu Longhou in his book of 1921 already showed the shin being perpendicular to the ground. Yang’s improvement in the later years was conforming more to his father’s teaching.

See again the photographs of Tung Huling in "T’AI CHI," February 1993, how the combination of the rear foot angle, knee alignment, and rounding of the thighs gives him the power and spirit in his Taijiquan.

(7) Importance of Front Knee Alignment in Making Forward Steps.

In making a forward step in the Yang style, one must first turn out the front toes, advance the trunk over the front leg, and then raise the rear foot to step forward. The position of the front knee, and the mechanism of turning out the front toes, play an important role in the smoothness of the forward movement and the continuity of strength and energy.

Chen Xin said, "The front leg is to brake, the rear leg is to push." Braking means using the front leg to stop your forward advancing strength. Experience tells us that unless the ground is extremely rough, as long as the front knee is not too far forward, and the front shin is perpendicular to the ground, the front leg can effectively brake or stop the advancing strength before the knee bends further forward. Before stepping forward, simply slightly raise the balls of the front foot, transferring the braking strength to the front heel, and applying a little pushing strength at the rear leg to rotate the hip joints sidewise. The front heel will become a pivot for turning out the toes and rotating the perpendicular shin and the upper body. The movement is simple and continuous without interrupting the flow of energy or the intent to advance.

If the front knee were bent over the front toes or further forward of the toes, it would be impossible to raise the balls of the front foot to transfer the braking strength to the heel. Certainly one cannot pivot at the heel to turn out the toes. The only solution would be to retreat the trunk and the front knee before turning out the front foot, and then advancing the body over the front leg again before picking up the rear foot to step forth. Although the intent is to advance, the movement requires retreating the trunk and the knee before stepping forward. Such interruption of the continuous energy is the worst case of "indentation and protrusion" which is strongly objected to in the Taijiquan classic. It also creates a gap in self-defense.

the 24-, 48-, and 88-posture Taijiquan designed by the Chinese government and published in the 1950’s, teach the postures "Wild Horse Parts Its Mane" and "Brush thigh and Press Forth Palm" by explicitly telling a reader to (a) first retreat over the rear leg and shift back the center of gravity; (b) raise front toes and balls to turn outward; then (c) advance the trunk to bend the front knee again to step forth the rear foot. The photographs in the original publication showed that the front knee was bent over the toes, sometimes even further forward than the toes. When we teach movements that disrupt the continuous energy to correct the mistake of over-advancing the knee, the students will never learn to use the braking strength in the front leg. When the discontinuity becomes a habit, they will also fail to realize the need to keep a continuous flow of energy throughout all the movements. This greatly reduces the health benefits of the exercise. When these series, designed by the Chinese government, were translated into English and published in the Unite States, many regarded them as standards. This had serious adverse effects on the art of Taijiquan in this country. Following these examples, a number of other Taijiquan series, also explicitly teach such back and forth movements in making forward steps.

Traditional Yang style Taijiquan books from 1921 to 1982, written by Xu Longhou, Yang Chengfu and Yang’s direct students such as Chen Weiming, Tung Yingchieh, Fu Zongwan and Ku Liuxing all do not teach such movements that interfere with the continuation of energy flow. Many instructors today continue to teach the knee-over-toes formula, requiring retreating the body before taking a step forward. This seems unreasonable especially after Yang Chengfu had expressly taught to keep the shin perpendicular to the ground.

(8) Body Alignment.

Yang Chengfu’s forward bow stance is always with his upper body inclined forward. From the rear heel through the rear leg and hips to the back up to the shoulders would form a forward inclined straight line about 60 degrees with the ground. The only exception is the rear knee that is not locked buy slightly bent sidewise, in the same angle as the rear toes. This is consistent throughout his early and later forms. Photographs of Xu Longhou, 1921, was the same way. However, in Yang’s 1925 photographs, his shoulders, back, hips and legs often had certain irregularities. Many of the early photographs also showed his head leaning back while the body was forward inclined; thus the neck and the spine were not in line. This is shown in his "squeeze" (in "Stroke Peacock’s Tail"), "Brush Thigh and Press Forth Palm," "Carry Hammer Forward" and "Hammer under Elbow." In "Fan Through Back," his upper body was vertical but the head leaned back. In the 1931 pictures however, from the rear heel through the rear leg, the hips, the back and the head were all very well aligned. From his earlier photos, one could still detect from his external form when he was applying strength. In the later photos, he seemed to have full energy flowing through the whole body and his integrated supple strength was not expressed outwardly. It was certainly a higher level of accomplishment.

(9) Improvements after 1931.

Zeng Zhaoran first learned from Chen Weiming in Guangzhou (Canton) and then studied with Yang when Yang moved there. At the time, Yang was already quite ill. While Yang assigned his son, Yeung (Yang) Sauchung, to serve as Zeng’s coach, Yang was still able to answer Zeng’s questions. Zeng had this special privilege because he was one of the very few who were formally admitted as Yang Chengfu’s private students after following certain established Chinese formalities. So Zeng’s book has sections on a few postures discussing certain variations including Yang’s changes between the earlier and later years. Unfortunately, Zeng’s attention was concentrated only on the external forms of the hands. He did not attend to other refinements such as the foot alignment as discussed in this article. His assumption on the "golden Cock Stands on One Leg" posture was also based on his own speculation without consulting Yang. However, the book did describe two important changes made by Yang in his later years that were not included in Yang’s books of 1931 and 1934. Because these points involve improvements in strength application, they deserve special attention.

One of the changes in strength application was in the posture, "Conquer the Tiger." For this posture, Zeng wrote that in the earlier years, Yang taught that the thumbs of the upper and lower fists were to face each other upon completion of the posture. Later, he taught to point the thumb of the lower fist towards the abdomen. When Zeng asked Yang for the reasons, Yang answered that the applications remained the same except that his later method made the strength smoother. The forms of Yang’s fist in this posture as shown in his 1925 and 1931 books were identical.

His later modified method must have been taught for him by his son, Yeung (Yang) Sauchung, in Guangzhou (Canton) when Tung Yingchieh was also there assisting Yang in teaching classes. In Tung’s book of 1948, the two fists were exactly as taught by Yang in Guangzhou.

Experimenting with these alternative fist positions, one can easily find that circling the upper fist upward with the thumb facing downward give the upper arm a "nichan" twisting strength. In Yang’s published forms in 1931 and 1934, when the thumb of his lower fist pointed up, his lower forearm lacked this twisting strength and the energies of the two arms were not balanced. In his latest teaching, both forearms had the "nichan" strength, meaning the left forearm was twisted clockwise and the right forearm twisted counterclockwise. Not only did the energy of the forearms balance each other, it also balanced that of the two legs; each leg also retained a "nichan" strength (or inward twisting strength) to round the thighs and open the pelvis. If the thumb of the lower fist had faced up, the lower forearm would lack this twisting strength and became weak, destroying the energy balance of the whole body. As a matter of fact, in the 1921 book by Xu Longhou, who learned from Yang Chengfu’s father, the positions of the two fists were identical to those taught by Yang in Guangzhou. So Yang was simply returning to his father’s teaching.

The second change mentioned in Zeng’s book related to strength application was the Taiji sword postures "Embrace the Moon in Breast" and "tiger Embraces Its Head." Zeng wrote that Chen Weiming taught him to do these postures by raising the right knee with the right calf hanging straight down. When his "senior brother" Sauchung demonstrated this posture, both his right knee and his right foot were slanted at angles, looking very beautiful. Zeng asked Yang which was correct. Yang answered that his senior brother Sauchung was correct; but beginners must start by learning Chen Weiming’s way. It may be noted that Yearning K. Chen’s sword form for this posture, published in 1943, was the same as Chen Weiming’s. This shows that Yearning Chen did not learn Yang’s latest teachings.

Tung Yingchieh, had been assisting Yang to teach in Guangzhou until 1936. According to his teaching, the stationary left leg is bent, the right knee is raised and bent slanting rightward, right calf points toward the left, the sole of right foot faces left and inward, so that the whole right leg is rounded like a bow, almost horizontal. The thighs are rounded and each leg retains an outward twisting strength (or "shunchan"). The chest is hollow and both arms are rounded to embrace the sword with outward twisting strength) or "shunchan"). The strength in the upper and lower body is balanced so that the energy circulates through the whole body with a feeling of fullness. Eyes look forward with full attention.

"The mental state is like a cat about to stalk a mouse," ready to pounce, exactly as stated in the Taijiquan classic. The external beauty is an expression of the balanced full energy from within. His teaching is exactly as Yeung had demonstrated to Zeng in Guangzhou. If one hangs down the right calf, toes pointing to the ground, the form becomes weak and there will not be any balanced twisting strength nor the fullness in energy and spirit.

Zeng’s book said that beginners should start to learn the sword form with the right shin straight down. This is unnecessary. If beginners who learned the barehanded Taijiquan always draw an arc to circle a moving foot close to the calf of the stationary leg before stepping into any direction, the twisting strength ("chansijing") at their legs. When they correctly do the posture "separate feet", they are already twisting the legs outward ("shunchan") to separate not only the feet but also the two thighs. They just apply the same principle to the sword form.

(10) Conclusion.

Currently, there are many variations of the Yang style Taijiquan. One of the reasons for such diversity is because Yang Chengfu improved his Taijiquan continuously. Students who learned from him at different times would learn and teach different variations.

By analyzing the changes between his early and later forms, one can see the integrity of this art in his later years and reduce unnecessary confusion and disagreements. In the preface of Yang Chengfu’s 1934 book, he said, "Looking into my art of a decade ago, it was no match for the present, showing the prospect for boundless personal improvement."

From the comparisons in this article, one can see that over a decade, he had made great strides in improving the art in various aspects and had never stopped improving himself. When he said that here was "the prospect for boundless improvements," it was certainly applicable to him. Were he to live another decade, his art would definitely have improved even more.

In corresponding with one of Yang Chengfu’s direct students, Ku Liuxing in Shanghai, the author mentioned some of the differences of Yang’s early and later forms. Ku urged the author to present the comparisons in an article. The author never had the opportunity to meet Yang Chengfu, so he could only base his observations and conclusions on photographs and written information found in other literature. the author hopes that Ku and other Taijiquan experts can seriously and objectively correct any error and supplement this article with additional information; so that we can further understand the evolution of the Yang family Taijiquan.

This article, originally in Chinese, was first published in "Tai Chi Chuan Journal", No. 62, April 1989 (Kao Shiung), and in "Wulin", No. 102, March 1990 (Guangzhou).

After reading this article, Yang Zhenduo, the third son of Yang Chengfu, wrote the author from Shanxi province, China, that he fully agreed with the author’s comparisons of his father’s Taijiquan in the early and later years. He also fully agreed to the explanations justifying Yang Chengfu’s various changes as results of continuous improvements.

This translation in based on the author’s partly revised edition of his Chinese article.