Lineage

Location

Pictures

Books/Videos

|

Home

Page Lineage Location Pictures Books/Videos |

|

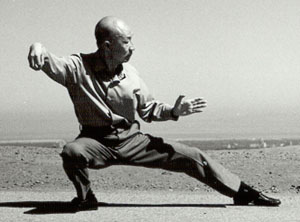

Wu Ta-yeh in Single Whip Low Posture. Rear knee is over rear toes, both pointing rearward, rear heel not raised. Front toes point directly front, not sidewise. Front knee slightly upward, not sidewise. Trunk retreated, perpendicular. Left shoulder and arm naturally dropped from gravity without strength. No knee pain. See section 6 below. |

A sample survey of 216 American Taijiquan (T’ai Chi Ch’uan) instructors by Jay Dunbar for his 1991 doctoral dissertation showed that 60 percent of the teachers believed that knee injury can be a result of Taijiquan. (T’AI CHI, August 1992) In Taiwan, there are persons making knee braces according to the specification of Taijiquan teachers for sale to the practitioners. This shows the seriousness of the same problem there. In Mainland China, knee pain in Taijiquan is seldom seen in writing.

This article attempts to identify the main causes of knee pain in Taijiquan, and explain how knee pain is avoided in the traditional Yang style as established by Yang Chengfu in 1931. This kind of comparison should be useful because, according to Dunbar's sample survey, "one-third" of the respondents taught only a traditional Yang style form. The implication is that there are other instructors also teaching the traditional Yang style along with other styles. Moreover, many of the new styles developed after the Second World War claim to be derivatives or modifications of the Yang style.

(1.) Knee pain is not inherent to the well-established traditional Taijiquan.

Chen Fake (1887-1957) practiced the Chen style Taijiquan 30 rounds a day. Even after 40 years of age, he still practiced 20 rounds a day. His grandson Chen Xiowang, still practices 30 rounds a day at present. It is well known that the Chen style is the most strenuous among all Taijiquan styles. Any knee pain will prevent them from practicing like this.

The centenary Taijiquan expert and author Wu Tunan (1885-1989) had very poor health in childhood. From age 9 to 15, he learned the Wu style from the founder of the school, Wu Jienquan. Then, he learned the Yang style for another four years with the elder brother of Yang Chengfu, Yang Shaohou. Teaching a private student in the student’s home, both teachers were very demanding. Yang Shaohou even asked him to do the exercise under a few large tall kitchen tables put together, to make sure that his stance was low enough. If Wu Tunan had developed any knee pain, his parents would have asked him to discontinue. As a result, after 12 years of the strictest discipline, his diseases were all cured and he became a Taijiquan teacher himself, living to 104 years old. The above facts show that, in the well-established traditional Chen, Yang, and Wu styles, there do not seem to be inherent reasons to cause knee pain.

Dunbar correctly stated that Taijiquan teachers must "distinguish externally imposed postures from movements that are truly natural, and follow the body’s own internal line of least resistance and best support." (T’AI CHI, August 1992.) with a history of the traditional Taijiquan of three hundred years transmitted through many generations of experts, evolution from repeated trial and error must have minimized the unnatural movements and conformed more and more to one’s internal line of the least resistance and best support.

The Yang style, however, after having modified many of the principles of the traditional Chen style, has gone through only a hundred years of development and improvement. And these improvements continued until the last ten years of Yang Chengfu’s life, who died in 1936. (See my article, "Yang Chengfu’s Earlier and Latest Taijiquan," T’AI CHI, April 1993.) Unfortunately, many of Yang’s students who learned before Yang’s major improvements in the 1930s continued to teach the Yang family’s old methods. Then, their own disciples often teach a hybrid system, mixing the old methods with the new, and this mixing sometimes caused knee pain. (See Section 6 below.) When mixing the earlier and later methods of the same style creates serious problems, any mixing of the styles which are more divergent in methods may have worse consequences, even if it may not create knee pain.

From the fact that it took 100 years to improve the Yang style, it is not surprising if it will take more years from this time onward to further improve some of the new styles developed after the Second World War.

Besides mixing methods and styles, individuals who learned the established traditional styles incorrectly, of course, may still develop certain forms of knee pain, as illustrated in Section 7 below. Errors from incorrect learning of the established traditional styles, however, can be easily rectified once pointed out.

(2) Gravitation weight and knee alignment

There have been many new Taijiquan series developed after the

Second World War. While most of them claim to be derivatives or

modifications of the Yang style, some of them prescribe the following

formula for a forward stance:

a. The front knee is not further forward than the front toes,

but should be on the same perpendicular line with the front toes.

b. The front foot carries 70 percent of the body weight, and the

rear foot, 30 percent.

I have a habit of always personally experimenting with any Taijiquan method and then ask my students to repeat it before I write about it. After reading Dunbar’s article on knee pain, I did the experiment myself. I put my front foot on a bathroom scale and bent the knee exactly over the toes. I raised my rear heel to support myself with the toes and ball of the rear foot so that I could adjust my body forward and rearward until the bathroom scale registered 70 percent of my body weight. In moments, I felt knee pain and stopped the experiment. The pain was below the kneecap, not too serious, but persisted for more than a week, coming fast and leaving slowly. Of course, since I am over 85 years old, I should not have done this experiment personally. When I told the story to my students, I did not dare to suggest them to repeat it; instead, I warned them not to try it, in order to release my responsibility.

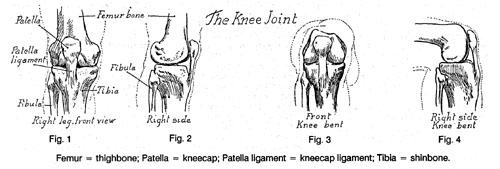

I found the reason for this pain from the drawings of the knee joint in Dunbar’s article, and I thank him for supplying me some additional drawings for this article. Figure 1, right leg, front view, shows how the shinbone is connected to the thighbone. The kneecap is attached to the thighbone, and the kneecap ligament is extended downward from the kneecap and attached to the shinbone. Figure 2 shows the same thing looked at from the right side. In figures 3 and 4, when the knee is bent to 90 degrees, the kneecap ligament is partly extended, with the perpendicular shinbone supporting the end of the thighbone directly from below. Based on Figure 4, we may imagine that we stand on the ground, bending the knee over the toes, so that the shinbone is forward inclined, angle with the thighbone about 60 to 70 degrees. The kneecap ligament is stretched or lengthened much more than in figures 3 and 4. The shinbone is now no more perpendicular to support the end of the thighbone directly from below. In this alignment, if we place 70 percent of our body weight on the thigh, the ligament pains. This is exactly what I have experienced, when the pain was at the ligament below the knee.

Michael Heim found soreness and irritation around the kneecap. (T’AI CHI, October 1992.) This must be the result of repeated practice. It may also come from the lateral misalignment of the knee when turning leftward or rightward.

I realized that my naive experiment was not relevant to Taijiquan, although I confirmed one source of knee pain. In the experiment, I had to stand with the two feet close together so that I could raise my rear heel to lean my body forward until my front foot bears 70 percent of my body weight. In Taijiquan, when the rear foot is far behind, this cannot be done unless the trunk leans very much forward. So I asked my students to do some more realistic experiments. Since most of the teachers who emphasize the body weight distribution prescribe to always have a perpendicular trunk, even in a forward stance, this perpendicular trunk is used.

We placed a large wooden board on the ground with the thickness about the height of the bathroom scale. In turn, each student stood with the rear foot on the wooden board and front foot on the bathroom scale, posing in the form of a forward bow stance, front knee over toes. We started with the trunk, from the tailbone to the shoulders, perpendicular to the ground. The average body weight on front foot was 49 percent. When the trunk, from the rear knee to the shoulders, was perpendicular, the average body weight on the front foot was 46 percent.

Sophia Delza has taught the Wu style Taijiquan in the United States for more than three decades. She told me that in a forward form of the Wu style, the front foot generally carries 70 percent of the body weight. But their trunk leans forward about 45 degrees most of the time, not perpendicular. With their front shin about perpendicular, supporting the thighbone directly from below, they do not experience knee pain.

It appears that nobody who used the formula of front knee over toes with a perpendicular trunk ever tried to find the actual percentage body weight on the front foot as we did, so that the 70 percent figure with a perpendicular trunk can be only a concept never actually followed. Of course, since I and our students did not have the experience in the styles in question, our speculation may not be correct.

Let us assume: (1) the front knee is exactly over the front toes, and (2) no more than 50 percent of body weight is on the front foot. This means that, because of the knee alignment, the kneecap ligament may still be overstrained. Can this knee alignment with less than 50 percent of body weight cause knee pain if practiced frequently? Any experiment to answer the question will require prolonged practice like this, and we did not do it, leaving the question unanswered.

This knee-over-toes alignment is, however, relevant in making footsteps, as can be seen in Section (4) below.

(3) Dynamic strength and alignment of the whole body.

Self-defense is to apply strength in various ways, and the solo exercise is based on self-defense principles. Hence, all Taijiquan classics place great emphasis on strength, but not on body weight. In fact, none of the Taijiquan books published before the Second World War ever mentioned body weight, or percentage distribution of the body weight.

Strength is actively applied by the performer toward any direction. If you do not apply your strength, it is zero. If you apply it, it can be anything up to your own maximum. And you can increase your strength through training. You can press your two palms toward any two directions, but the aggregate strength applied at the two palms is not fixed.

Body weight is from the gravitation force toward the ground, not directly related to the strength applied by the person performing the exercise. There is only one direction of the gravitation force, straight downward, and your total body weight is fixed until you gain weight. Except by varying the percentage distribution of your body weight carried on each foot, there is not much else you can manipulate about your body weight.

Chen Xin (1848-1929) wrote, "the front leg is to brake, the rear leg is to support."

He also said, "the front is light and the rear is firm." What he referred to was the relative strength, not body weight. This is in agreement with Tung Yingchieh (1886-1961) of the Yang style, who wrote in 1948, "Strength is rooted at the rear heel." Instead of the percentage distribution of the body weight on the two feet, attention of the Chen and Yang styles is paid to the way one’s strength is applied at the legs, and this can be a forward strength or a rearward strength.

Yang Chengfu, 1931. Long foot step, low stance.

Front leg served as a brake, shin almost perpendicular to ground.

Rear leg served as support, toes pointing 80 degrees sidwise.

Trunk 60 degrees forward inclined from rear heel through the

trunk to the head, forming a continuous straight line, with the

exception that the rear knee is slightly bent sidewise in the

same angle as the rear foot. Right forearm presses forward, left

forearm pressed downward, both hands assumed a sitting wrist

form. Energy of the whole body is well balanced. Yang Chengfu, 1931. Long foot step, low stance.

Front leg served as a brake, shin almost perpendicular to ground.

Rear leg served as support, toes pointing 80 degrees sidwise.

Trunk 60 degrees forward inclined from rear heel through the

trunk to the head, forming a continuous straight line, with the

exception that the rear knee is slightly bent sidewise in the

same angle as the rear foot. Right forearm presses forward, left

forearm pressed downward, both hands assumed a sitting wrist

form. Energy of the whole body is well balanced. |

Yang Chengfu said the knee is bent up to a point when the shin is perpendicular to the ground. Further forward than this is over-application of strength. ("talk on Practicing Taijiquan.") What he referred to is the front leg in a forward bow stance and what is over applied is the forward strength from the rear leg. (the photo shown on this page was taken at least several years before his "Talk on Practicing Taijiquan.") The Chen style expert Hung Junseng wrote in 1984, the two kneecaps are to be in line with the respective heel of the foot. He explained that further forward will result in forward inclination of the shin, resulting in stagnancy and difficulty in turning. The criterion for the two styles is identical. When the knee is lined up with the heel of the foot, the shin is perpendicular.

When we use this knee alignment, the end of the thighbone is supported by the perpendicular shinbone directly below it, without overstretching the ligament below the kneecap. There is no cause of knee pain in ordinary usage.

In experiments with a bathroom scale, our students stood with a body alignment like Yang Chengfu as illustrated above: front shin almost perpendicular; trunk forward inclined, from the rear heel through the hips to the shoulders and head, forming a 60-degree forward inclined straight line; rear leg as support; front leg as brake; forward strength applied to the forward extended arm. The average percentage body weight of our students on the front foot was about 60 percent. But there was no knee pain. In the Yang style, therefore, the front foot bears a greater percentage body weight from gravity than the alternative when the front knee is over the toes, trunk perpendicular, and without applying any forward strength (60% vs. less than 50% of the weight on front leg).

The knee pain is therefore not from the body weight as such. If there is such a pain with less than 50 percent of body weight on the front foot, it must be from the misalignment of the knee to strain the ligament below it.

Readers who want to experiment with Yang Chengfu’s alignment would follow his form carefully, attending to all details. In the forward bow stance, (1) his footstep was fairly long; (2) his rear leg served as support, toes pointed 80 degrees sidewise; (3) his front leg served as a brake, shin perpendicular to the ground; (4) his trunk was about 60 degrees forward inclined; (5) his rear leg, from the rear heel to the hips, was also 60 degrees forward inclined, joining the trunk in an uninterrupted straight line, with the only exception that his rear knee was slightly bent 80 degrees sidewise, in line with his rear foot , in order to retain a springing action, with the preparedness to take various actions. Thus his forward strength was fully transmitted from his rear foot through his rear leg and his trunk to his forward extended forearm. With this body alignment and strength application, the energy at every part of his body was well integrated, with balance and stability. Yet, he could move forward, rearward, or sidewise easily at will. In the rest of this article, one will see how his body alignment and his method of strength application gave him the mobility and power, without knee pain.

(4) Methods of forward steps.

Improper method of making forward footsteps may cause knee pain. In the bow stance of the Yang style, the rear foot is pointing sidewise while the front foot is pointing forward. Before making a forward step, one must first turn out the front toes to anticipate its being a rear foot, before raising the other foot for stepping forward. Such turning out of the front toes is a special characteristic of the Yang style, not shared by the other styles before the Second World War, such as the Chen, Wu, Hao, and Sun styles.

In the forward bow stance of the traditional Yang style, when the trunk and rear leg form a continued 60-degree forward inclined straight line, front shin perpendicular to the ground, so that the front leg serves as a brake and rear leg serves as support, making forward footsteps with loosened joints is very simple and neat.

Suppose you stand exactly like Yang Chengfu’s photograph, with a fairly long and low foot stance, left leg at the front serving as a brake, shin perpendicular. The right leg at the rear for support, from the rear heel through the tailbone to the shoulders, is a 60-degree forward inclined straight line. When you want to make a forward step, you simply continue a very little forward strength at your right rear leg by slightly reducing the sidewise bending of the rear knee to push your right hipbone a little bit forward. with loosened joints, this is done with the ball at the top of your right hipbone, which fits nicely in the socket of the right hipbone, to serve as a torque to convert the 60-degree upward strength into a horizontal, circular strength to rotate the hips counter-clockwise. with the left front toes and ball of the foot slightly raised to transfer the braking strength to the front heel, this will turn out your left thigh and automatically rotate your whole perpendicular left shin leftward, pivoting at the heel until the toes are turned to the desired angle. As soon as the front toes are turned out, the continued forward strength at the rear leg will allow you to advance the trunk and step forth the rear foot. Therefore, from the previous forward posture, you continue to use the forward strength of the rear leg to turn out the front toes and step forward with the rear foot without discontinuing your internal energy, or qi. This uninterrupted qi energy, which circulates through all meridians and collaterals in your whole body for 20 or 30 minutes in each round of the exercise, is the reason why Taijiquan is recognized as the best of all moving qigong. In the process of turning out the front toes, since the knee, the shinbone, and the heel of the front foot rotate as a single perpendicular shaft, there is no lateral twisting of your knee or strain at the knee ligament to cause knee pain. This is the way we have been teaching in Palo Alto since 1972.

If you always have a correct body alignment and your movements are based on supple, dynamic, integrated strength, braking with the front heel and pushing with rear leg, then, with a little training, any person can effortlessly pivot the front heel to turn out the toes of the weighted front foot up to 90 degrees or more without pain. When you are skillfully trained with this mechanism and everything becomes a habit, your intention of twisting your waist for stepping forth your rear foot will automatically produce the little pushing strength at your rear leg to initiate all the movements to start your forward step. You do not think of the details each time.

If your front knee is over the toes or in any way the shin is forward inclined, the above method cannot be used. As written by Hung Junseng, quoted in Section (3), this misalignment makes your turning difficult. You must retreat your trunk and knee sufficiently before turning out the front toes. In principle, this procedure should be able to prevent knee pain. The problem is, how much one should retreat the trunk and the front knee, and what is the mechanism of turning out the front toes.

Experiments found that, even when you have retreated the front knee until it is over the heel, if your trunk, from the tailbone upward, is perpendicular to the ground, so that the trunk is not in line with the forward inclined rear leg, as in Yang Chengfu’s photographs, but break up at the tailbone or rear knee, the forward and upward pushing strength at the rear foot cannot be transmitted through the broken line from the rear leg to serve as a torque to rotate the hipbones for automatically rotating the perpendicular shin to turn out the raised front toes. Here the method or mechanism of transmitting the twisting strength at the soft waist to turn out the knee and the toes is crucial. Such transmission, not through bone to bone, may be done differently by different persons. Some form of the transmission may involve lateral misalignment of the knee and straining the knee ligament. doing something like this repeatedly may create knee pain. If your trunk, from the rear knee upward, is perpendicular to the ground, you have even less torque to rotate your hipbones. A different body alignment requires a different method.

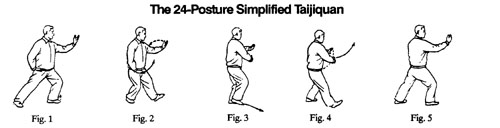

The 24-posture simplified Taijiquan, and the related 48- and 88-posture series published by the Chinese government seem to solve this source of knee pain effectively. The accompanied drawings show that, from a forward posture (Fig. 1), they retreat the trunk over the rear leg until the front thigh, knee, and shin form a downward reclining straight line about 60 degrees toward the ground (fig. 2), in order to raise the front toes very high for turning them sidewise before advancing the rear foot and the trunk again. Since the knee is almost locked with the thighbone and shinbone, rotating at the head of the thighbone to turn out the thigh and shin as a single unit should not create any misalignment of the knee to cause knee pain. Such procedure involving forward-backward movement, however, does not allow you to continue your internal energy for the high quality moving qigong. In self-defense, it is also most vulnerable. When students are taught to create artificial discontinuity, they will never pay attention to continue their energy from posture to posture. Unfortunately, English books and video tapes on these series call them "standard" or "orthodox" Taijiquan. some even call them Yang style.

Xu Longhou, 1921. Long foot step, front shin about perpendicular, rear toes pointed 45 degrees sidewise. From rear heel to the shoulders, forms a forward inclined 60 degrees forward inclined line. For Section 6, B, note that he had a wide lateral distance between the two heels, front toes partly turned in, approaching "parallel feet." This will reduce knee pain when trunk is shifted rearward. (see T'AI CHI, April 1993.) |

"Dan Lee believes the Yang seems to imply a slightly rocking back just before turning the front toes out and stepping forward with the back foot." ("A Suggestion for T'ai Chi Knee," by Michael Heim, T’AI CHI, October 1992.) There is not such an implication. The traditional Yang style always used a very long foot stance with the trunk forward inclined. This can be seen in the 1921 book of Xu Longhou, who was a student of Yang Chengfu’s father, Yang Jianhou. His pictures are the earliest ones available for the Yang style. With a much longer foot stance than Yang Chengfu’s 1931 photographs, trunk forward inclined in a continued line with the rear leg, and front shin perpendicular, he could apply just a very little pushing strength at the rear foot for transmission diagonally upward through the thighbone to rotate the hipbones to turn out the front thigh, knee, shin, and toes, as a single unit.

Another evidence is in a recent book "Taijiquan," by Tsao Shu-wen, Hong Kong, 1992. Tsao is a fourth generation disciple of Yang Chengfu’s elder brother, Yang Saohou. His front shin is perpendicular to the ground, and he does not retreat his trunk before turning out front toes for making forward steps. Since both Xu and Tsao are not directly linked to Yang Chengfu, it is evident that the traditional Yang style before Yang Chengfu did not retreat the trunk before advancing.

Tsao also wrote in his book that, "recently some persons choose to retreat the trunk toward rear leg before turning out the front toes....But the older generation masters always directly turn out the front toes."

Yang Chengfu’s grandnephew, Fu Zhongwen (born 1907) started to learn with Yang in 1916, and represents Yang’s earliest teaching ever known. And he does not recognize his granduncle’s improvements in the 1930s. (See my article in T’AI CHI, April 1993.) In both his books of 1963 and 1989, he did not retreat his trunk before turning out his front toes to advance his rear foot. In fact ,not a single book published before the Second World War taught to retreat the trunk before advancing.

The rocking back is necessary when (1) the front knee is too much forward, (2) the foot stance is too short and high, or (3) the trunk is perpendicular, breaking the continued forward inclined line with the rear leg. All these prevent the transmission of the pushing strength from the rear leg to produce the torque to rotate the hipbone to turn out the front thigh, shin, and foot.

The above is why the classic prescribes to start the training with the extended form before learning the compact form, which uses a shorter and very low stance. This is the meaning of the word "compact." The body alignment, the strength application, the twisting characteristic, the circling of the arms with plenty space below armpits and all other subtleties are the same. A compact form does not mean just standing tall with a short foot stance and without applying strength. Once a person is well trained in the extended form with all the details, he can in the advanced stage train himself to do the compact form. Yang Chengfu used a slightly more compact form in 1931 than in 1925 because he had passed the training stage in the extended form. Yet he still used a much longer and lower stance than many modern practitioners of the Yang style.

If you start to learn Taijiquan in the extended form with long foot steps, you will feel that it is strenuous to bend your front knee too much forward, certainly not over the toes. With the braking strength at the front leg, it is easy and almost automatic to stop your forward moving knee at the time when the shin is perpendicular to the ground. The breaking strength at the front leg and the pushing strength at the rear leg give you the preparedness to move agilely toward any direction. Besides making forward steps, the braking strength at the front leg enables you to retreat any time, and the twisting strength at the waist allows you to turn sidewise in various ways. Combining all these strengths, you have the physical exercise and the various self-defense capabilities in different forms.

The real compact form in the advanced stage based on the Yang style principles can be illustrated with the photographs of Master Tung Huling when he demonstrated the "Yingchieh Fast Taijiquan." One can see that his foot step is long relative to the height of his stance. With the front leg as a brake, his front shin is no more forward than the shin perpendicular to the ground even when he was applying his forward strength, so that he can use the front heel as a brake to turn out his front toes with just a little continued push with the rear leg without rocking back his body.

The illustrations show that, from #28, he was advancing his left foot forward. In #29, he continued his pushing strength with his rear right leg to advance his trunk. With the braking strength at his left front heel, the forward movement stopped when the front shin was almost perpendicular. Then, continuing the pushing strength at the rear right leg in #30 and the continued braking strength at left heel, his left front toes were automatically turned out, pivoting at the heel. Still continuing this pushing strength, he stepped forth his right leg in #31. After he has further advanced his trunk and front knee in #32, he was ready to turn out the right front foot to make the next forward step with the left rear foot. There was no interruption of the forward energy in the continued forward steps. Doing like this for the whole exercise, one continues the internal energy, which circulates through the whole body, from the very beginning to the very end of the solo exercise to receive the utmost health benefits of the moving qigong.

(5) Turning on a weighted foot and dynamic strength

Dunbar mentioned the turning on the weighted foot in the Chen style. (T’AI CHI, December 1992.) As described in the last section, when you use Yang Chengfu’s form, trunk forward inclined, shin perpendicular, and front foot carrying 60 percent of the body weight, there is no problem of directly turning out the front toes. It all depends on the correct alignment of the whole body and the correct application of the dynamic strength. The problem arises when the front shin is forward inclined when the trunk is perpendicular, breaking the smooth line with the rear leg, and when your attention is on the shifting of body weight without applying dynamic strength. You have difficulty even when the front foot carries less than 50 percent of body weight. The easiness of turning out a foot does not depend on the weight at the foot but on the perpendicular shin, the correct alignment of the whole body, and the dynamic strength correctly applied by the practitioner.

In the traditional Yang style solo form toward the end of Part II, after you have kicked right foot toward east, the transition to the next posture "Twin Mountain Peaks Smash the Ears," requires you to continue hanging your right foot in the air to pivot at left heel to turn left foot and the whole body rightward by 45 degrees. You keep the right thigh parallel to the ground, hang the calf, toes down, and slightly raise the toes and ball of left foot to transfer the whole body weight to left heel. Then, you twist your waist and hips a little rightward to pivot at left heel to spin the perpendicular trunk with 100 percent of your body weight. Through practice, you may not have much jerking during the turning.

Also, after you do "Separate Left Foot" in Part II, Yang Chengfu taught to keep the left foot in the air and pivot at right heel to turn right toes leftward, from pointing east southeast to pointing north-northwest, a total turning of about 110 degrees carrying the perpendicular trunk with the whole body weight. You do it in the similar manner as you turn rightward to do the posture "Twin Mountain Peaks."

In the fast Taijiquan, there are occasions when you raise right foot and pivot at the left heel to turn left foot and the whole body 270 degrees rightward, before right foot touches ground. Turning at higher speed, you find it easier. When you spin with full weight on one heel, you apply your dynamic strength to spin your almost perpendicular shin, but you can slightly lean your trunk to improve stability and gain momentum. It is believed that the Chen style uses much more dynamic strength than the Yang style. In Taiji sword and Taiji falchion, the swinging of the heavy weapon allows you to apply the dynamic strength much easier and more effectively in spinning your body.

Readers who still puzzle may observe a ballet dancer who pivots at the toes of a foot to spin the whole body, with the shin and thigh perpendicular to the ground carrying 100 percent of the body weight. Once you ignore the body weight distribution and apply the dynamic strength in various ways to the correctly aligned body, with loosened joints, you will be able to do many more things for health and self-defense, moving lively with energy, spirit, and aesthetic appeal.

(6) Rear foot angle.

Improper rear foot angle may cause knee pain. In my article on "Yang Chengfu’s Earlier and Latest Taijiquan," (T’AI CHI, April 1993) I explained two systems of the rear foot angle in the Yang style. Let us first compare these two systems:

System A. Suppose you assume a bow stance facing west, right front foot pointing west, left rear foot pointing about 80 degrees south of the west east line. The lateral distance between the two heels is about the width of your shoulders. This is about Yang Chengfu’s latest foot alignment as he published in his 1931 book.

System B. When you face west, your left rear foot points about 45 degrees south of the west-east line. You take a wide lateral footstep with your right front foot to your right and put it at the west northwest direction, toes point west southwest. This is about the foot alignment adopted by the old Yang style up to the 1920s. (See Xu Lunhou’s drawing in Section 4, and explanations below that picture.)

In system A, when you retreat your trunk rearward toward the east, you bend your rear left knee sidewise, also pointing 80 degrees toward the south, so that the angle of your rear knee is the same as that of your rear toes. Your weight is mainly on the rear leg. There is no knee pain.

In System B, when you retreat your trunk with a wide lateral distance between the two heels, you do not shift toward direct east, but from about west northwest to about southeast. The angle of the left foot relative to the diagonal line of movement, is fairly similar to Type A when you retreat your trunk toward the direct east. That is, the effective rear foot angle, in relation to the line of movement, is more like 70 to 60 degrees, not 45 degrees. You bend the left rear knee over the rear toes, knee with the same angle as the left toes. The knee pain, if any is not serious.

System C. Suppose you put your left rear foot in the same position as in system B, or pointing 45 degrees south of the west-east line. But you place your right front foot at the same place as you do in system A, toes pointing front (direct west), lateral distance between the two heels about the width of your shoulders. this is a hybrid foot alignment, mixing the Yang style of the 1920s with that of 1930s. When you retreat your trunk from the direct west toward the direct east, you have to bend your rear knee much more forward than in System A. You will hurt your knee if you assume a low stance.

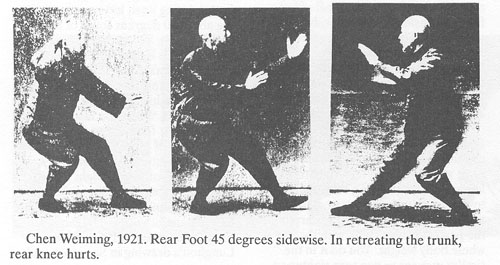

Chen Weiming’s photographs of 1925 illustrate this kind of foot relation. One can sense that he was hurting his rear knee. As a matter of fact, Chen was supposed to follow System B, like the drawing of Xu Lunghou in Section 4 above. But unlike Xu the lateral distance between Chen’s two feet was not enough, so that he was actually doing more like in System C. (See photos below.)

The 45-degree rear foot angle, in the setup like system C, hurt the rear knee even more during the fixed step hand-pushing when you repeatedly bend your rear leg to shift your trunk backward. This is different from the Wu style when they raise their front toes each time as they retreat their trunk over rear leg. A common practice in using the system C foot alignment at present is to adopt a short and high stance both in the solo exercise and in the two-person operation. The knee pain problem is not solved, but partly evaded.

It may be pointed out, in the posture "Single Whip Low Form," or "Serpent Creeps Down," you turn your rear foot to an extra wide angle, toes almost pointing to your rear. (See photo page 2) You bend your legs very low, rear knee turned in the same angle as rear foot, trunk fully retreated and sit perpendicularly over the rear leg. When most students can do it with a little practice, it shows that the wider the rear foot angle, the easier you can bend lower and sit over rear leg without hurting the rear knee, provided that your rear knee angle coincides with your rear foot angle. Of course, in a forward stance, if your rear angle is too wide, you have difficulty in applying your forward strength. This is the reason of using the 80-degree rear foot angle for general purpose.

An important difference between the 80-degree and 45-degree rear foot angle is in the application of forward strength. In Taijiquan, strength is started from the rear heel. If the rear foot is 80 degrees sidewise, you can apply your forward strength from the rear heel irrespective of the length of your foot step, and you can repulse your opponent far away. If your rear foot points 45 degrees sidewise and you have a long foot step like Yang Chengfu, your forward strength will not start from your rear heel, but from the side of your rear foot below the large toes. Such forward strength is very weak. This may be why persons using the 45-degree rear foot angle choose to assume a perpendicular trunk with short foot stance, so that they can apply their strength from the whole rear foot for uplifting an opponent.

(7.) Lateral knee alignment.

A knee is constructed for bending in the same directions as the toes. Any sidewise turning of the knee is accomplished through the turning of the thigh through the rotation of the ball at the top of the thighbone. Look at the knee joint drawings (1) and (2) in Section 2 above. Sidewise turning of the knee without moving the thighbone is trying to lean the shinbone leftward or rightward. The knee is not constructed for this purpose.

In the Yang style forward stance, when your right rear leg is forward and upward inclined, with the toes pointing 80 degrees sidewise, it is the ball at the top of the right thighbone which rotates the thigh and shin 80 degrees clockwise. When you also slightly bend your right rear knee, it is natural that the knee also points 80 degrees sidewise, in the same angle as your rear toes. There is no misalignment between the knee and the toes, and there is no knee pain. This is the way you always do a forward bow stance. The slightly bent rear knee retains a springing action of the rear leg and allows you to apply your optimum forward strength. If you bend your rear knee in a 60- or 45-degree angle, there is lateral misalignment. You have less springing strength at the leg and can apply a smaller forward pushing strength. You may also develop knee pain.

In a forward stance, if your trunk, from the rear knee to the shoulders, is perpendicular to the ground, and you want your body and shoulders to face your direct front for effective application of your forward strength, it is very difficult to bend your rear knee sidewise in the same angle as your rear toes, whether 80 degrees or 45 degrees. the tendency is to bend your rear knee downward and forward. The wider is your rear foot angle, the worse is the toes-knee misalignment. this may be one of the reasons for using a narrower rear foot angle for such a perpendicular trunk. In fact, some disciples of this school use a rear foot angle of less than 30 degrees. Of course, when you assume a tall and short stance, place very little body weight on rear foot, and refrain from applying any forward strength at rear leg, you can minimize knee pain from such misalignment.

In the traditional Yang style, lateral misalignment of the knee occurs when students did not lean correctly. This happens especially in a rearward bow stance when their rear toes point 80 degrees sidewise but their knee points something like 45 degrees sidewise. While in a forward stance when the rear leg is almost straight, a minor knee misalignment may not precipitate appreciable knee pain, such pain may become serious in a rearward posture when most of the body weight is borne by the bent rear leg, and this will strain the knee. You may feel more hurt during the hand-pushing, when the rear leg is repeatedly bent to carry the bulk of the body weight. From the very beginning of learning, students should be trained to always bend their rear knee 80 degrees sidewise, in line with the rear toes, whether in a forward or in a rearward posture. In retreating your trunk with right foot at the rear, if you always initiate your rearward movement by twisting your waist and hips clockwise, you will automatically start to bend your knee rightward, and this cannot exceed the angle of your rear toes.

In the old Yang style, there is a possibility of lateral misalignment of the knee when the rear toes point 45 degrees sidewise. Suppose you start from facing west to do the posture "Stroke Peacock’s Tail," with a 45-degree rear foot angle, left rear foot pointing southwest. When you turn body southward for doing "Single Whip," you have to turn your right foot leftward by 135 degrees with some difficulty, until right toes point southeast. During this transition when left toes point southwest and right toes point southeast, the toes of your two feet point toward each other in a 90-degree angle. Many persons will have their knees closer together than their toes, resulting in lateral misalignment between the knees and toes. Doing this repeatedly may create knee pain. (In the traditional Yang style, you repeat this movement 10 times in the whole Taijiquan series.)

In the above transition, your rear foot points 80 degrees sidewise, and you need to turn right foot leftward by only 100 degrees from "Stroke Peacock’s Tail," instead of turning 135 degrees. The angle between the two feet during this transition is about 20 degrees, not 90 degrees. In this relative foot position, you can easily train yourself to round the thighs to separate the knees over the toes, so that the shins are almost perpendicular, with minimum lateral misalignment of the knees. Rounding the thighs to open the pelvic joints is always aimed at an all postures and during transitions. The Yang style is designed for long foot steps. You will find that a long foot step allows you to fully shift your whole trunk leftward, perpendicular over the left leg. This makes it easier to turn in your right toes by 100 degrees during this transition. Readers may re-examine the photographs of Master Tung Huling in T’AI CHI, February 1993, and see how the rounding of his thighs helped him achieve the correct toes-knee alignment and how this gave him the energy, power, and spirit in his Taijiquan.

There are other occasions in which you may create knee pain. For example, if you cannot loosen your waist sufficiently to do the posture "Circle Hands Like Clouds," your intention to twist your waist may also turn your hips leftward and rightward to circle your hands, creating lateral knee misalignment. That is, when you twist rightward, the turning of your hips may turn your knees to the right of your toes, and when you twist leftward, your knees may be at the left of your toes. If you waist is pliable enough, you can twist your waist independent to the hips to circle your arms and hands without affecting the knee. If your pelvic points are loosened enough, you can also round your thighs to separate the knees in all parallel feet forms with perpendicular shins and without lateral misalignment of the knees.

(8.) Ending remarks.

We should all thank Jay Dunbar for his sample study of Taijiquan instructors and his calling our attention to the seriousness of the knee pain problem in American. Without his statistics, the problem may not be seriously considered for a few more decades to come. Once the various sources of knee pain are identified, any practitioner can easily experiment with the effective measures to eliminate them.

There are, however, causes of knee pain which are not solved in this article. The most important one is the method of turning out the front toes. In Section 4, I have described in detail the very simple and almost automatic mechanism in the traditional Yang style with loose joints. It is the use of the ball at the top of rear thighbone as torque to convert the diagonally upward strength at the rear leg into a horizontal, circular strength to turn the hip joints sidewise, and this is enough to effortlessly turn the perpendicular front shin, from the knee to the heel, as a single unit, without knee pain and without interrupting the internal energy. While such mechanism applied perfectly to the traditional Yang style body alignment with loosened joints and with its methods of strength application, it does not work if the trunk is perpendicular to the ground, breaking the continued forward and upward line from the rear leg to the trunk. It requires a different principle and mechanism. Since the author does not have experience in this kind of body alignment, it is hoped that readers who are conversant with the mechanism of turning out the front toes in such cases may share their knowledge with the general public to reduce the chance of knee pain. There must be other styles and other causes of knee pain unknown to the author. It may take a collective effort of authors and instructors to remove all the causes of knee pain to regain the credibility of Taijiquan, which has long been considered one of the best means to promote both the physical and metal health.