Lineage

Location

Pictures

Books/Videos

|

Home

Page Lineage Location Pictures Books/Videos |

|

A Diagrammatic and Experimental Elucidation

In my article in T’AI CHI, April 1993, I considered the enlargement of the rear foot angle by Yang Chengfu in 1931 "an important contribution generally ignored." I have explained in great detail the evolution process how and why the original Yang style 45-degree rear foot angle of the 1920’s was changed to about 80 degrees in 1931. It was not a casual, isolated change, but a major overhaul involving the coordinated changes in the width of the foot stance, the front foot angle, the direction of forward strength, and the nature of the braking strength of the front foot. All these, as well as the reasons for the change, were explained in detail in my April 1993 article. the English translation of that article, eight pages long, may not be carefully scrutinized by all readers. Stripping the historical development and the detailed justifications, this note concisely explains Yang’s change, and lets each reader experiment with the relative merits of the different alternatives. With such a concise presentation, it is hoped that readers may read my articles in April, "Yang Chengfu’s Earlier and Latest Taijiquan," and in June, "Causes of Taijiquan Knee Pain and Painless Methods," with better understanding.

When a rear foot angle is mentioned in writing, it is approximate only. for example, Yang Chengfu’s rear foot angle of 1931 ranged from 80 to 100 degrees.

(1) Diagrammatic explanation

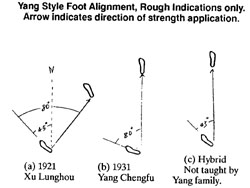

The accompanying diagrams illustrate

the alternative relative foot positions in the Yang style bow

stance. Diagram (a) shoed the tradition of the Yang style as practiced

up to the 1920’s. Relative to a north-south broken line,

the toes of the left rear foot point about 45 degrees sidewise,

or northwest. The right foot was placed very far to the east,

at your northeast, toes pointing north northwest. In this foot

position, if you apply a forward strength from the rear left foot,

the direction of your strength is not toward direct north, but

toward north north-east, as indicated by the solid line with an

arrow. Although the left rear foot pointed 45 degrees sidewise

when measured from the north-south broken line, it was actually

pointing 80 degrees sidewise when measured from the direction

toward which your strength is applied, as indicated by the arrow,

along the solid diagonal line. In Yang style, the forward bow

stance is primarily for the application of a forward strength.

therefore, it is your rear foot angle relative to the direction

of your forward strength which is relevant.

The accompanying diagrams illustrate

the alternative relative foot positions in the Yang style bow

stance. Diagram (a) shoed the tradition of the Yang style as practiced

up to the 1920’s. Relative to a north-south broken line,

the toes of the left rear foot point about 45 degrees sidewise,

or northwest. The right foot was placed very far to the east,

at your northeast, toes pointing north northwest. In this foot

position, if you apply a forward strength from the rear left foot,

the direction of your strength is not toward direct north, but

toward north north-east, as indicated by the solid line with an

arrow. Although the left rear foot pointed 45 degrees sidewise

when measured from the north-south broken line, it was actually

pointing 80 degrees sidewise when measured from the direction

toward which your strength is applied, as indicated by the arrow,

along the solid diagonal line. In Yang style, the forward bow

stance is primarily for the application of a forward strength.

therefore, it is your rear foot angle relative to the direction

of your forward strength which is relevant.

It was this foot placement which gained the name "parallel feet." This foot alignment is seen in the 1921 pictures of Xu Lunghou, who learned from Yang Cheng-fu’s father. Readers who want to know more about this foot alignment, including the reasons of doing so, may read my April article, sections (2), (3) and (4).

Diagram (b) shows Yang Chengfu’s foot position in his 1931 book. When your right front foot points directly north, your tailbone points almost directly north, and your rear left foot points about 80 degrees sidewise with the north-south line. the lateral distance between the two heels was reduced to shoulder width, front foot extended northward, toes pointing directly north. In this foot placement, the forward strength generated from your rear leg is directed north, toward the direction of your front foot.

Therefore, in terms of the direction of strength application, Yang’s so-called 80 degree rear foot angle in 1931 is equivalent to the so-called 45 degree rear foot angle in the 1920’s. Despite the different physical foot placement, the effectiveness of strength application remains similar.

Diagram (c) shows a hybrid foot position. the left rear foot is placed exactly like Diagram (a), toes pointing northwest, 45-degrees with the north-south line. But the right foot placement is the same as in Diagram (b), lateral distance between the two heels shoulder width, right foot extended north, toes pointing direct north. the direction of strength application is not diagonally toward northeast, like Diagram (a), but straight north, like Diagram (b). It is a combination of the 1921 rear foot with the 1931 front foot. When the rear foot forms an angle of 45 degrees with the direction of your strength application, it is a real 45-degree rear foot angle.

Foot alignment like diagram (c) has not been taught by the Yang family members. Although Chen Weiming was supposed to follow the formula in Diagram (a), his photographs showed that he did not have sufficient lateral distance between his two heels. the result was that he actually used foot stances somewhere between diagram (a) and Diagram (c). Most of his problems were created from this error.

Since both Yang Chengfu’s son, Yang Zhendou, and his teenager great grandson, Yang Jun, adopted the diagram (b) foot alignment, it is certain that this alignment will continue in the Yang family through the twenty-first century.

(2) Experiments with Forward Strength

To understand the implications of different rear foot angles in the traditional Yang style, the best way is to do some actual experiments.

Suppose you assume a forward bow stance like Yang Chengfu with a long footstep, front shin perpendicular, lateral distance between the two heels about shoulder width. Your trunk, from the rear heel through the rear leg, the tailbone, to the shoulders, is about a 60-degree forward inclined straight line, excepting that the rear knee is bent slightly sidewise in the same angle as the rear foot. You extend forward both arms, shoulders and elbows down, palms facing forward. This is the way you apply your forward strength in the traditional Yang style.

Now you ask a friend about your height to press his two palms upon yours. Keeping other aspects of your body alignment unchanged, you assume a different rear foot angle each time as follows:

(a) With reference to the direction of your front foot, turn rear left foot 80 degrees sidewise, rear knee also slightly bent 80 degrees sidewise, in the same angle as your rear foot. Ask you friend to gradually increase his forward pressure on your two palms. You transmit your strength from your rear foot upward and forward through your upward and forward inclined rear leg and trunk to your forearms and the forward facing palms. You resist with just enough strength to balance his strength. You will find that when your strength starts from your rear heel, you have the strongest support.

(b) Still with the same long footstep and the same forward inclined trunk, you reduce your rear foot angle to 45 degrees sidewise. In resisting the pressure from your friend’s palms, you will find that the forward strength from you rear heel becomes very small. Instead, most of the forward strength is from the ball and the inside edge of the foot, and the total magnitude of your forward strength is greatly reduced as compared to (a).

(c) Still with the same long footstep, the same lateral distance between your heels, and the same forward inclined trunk, you narrow down your rear foot angle to 30 degrees sidewise. You find even less forward strength from the rear heel, but from the toes and the ball of the rear foot. The total forward strength is very little.

The above assumed that you are copying the body alignment of Yang Chengfu to apply the forward strength. If, instead, you assume a very short foot stance, standing tall, and trunk perpendicular, you can apply an uplifting strength from your whole rear foot with a small rear foot angle, plus some upward strength from your front foot, even though the forward component of your strength is small. This is the way to uproot your opponent in a short and tall stance. While this is not the way Yang Chengfu taught, it shows that the effectiveness of a given rear foot angles depends very much on the direction and the way you apply your strength.

(3) Experiment with rearward stances.

Now, let us experiment with the rearward stances, body weight mainly on rear leg. These include postures such as "Step Back to Repulse Monkey," "Play the Guitar," "Fist Under Elbow," and the like.

Each person may do these postures differently. Having chosen a given posture for an experiment, you just do it according to you usual way. You note your approximate rear foot angle in relation to the direction of your front foot. Then, keeping all other variables constant, repeat the same posture by changing only your rear foot angle, alternately to 80 degrees, 45 degrees, and 30 degrees. You take note of the following points for each of the three rear foot angles.

a) How much rearward you can shift your trunk over rear leg.

b) How low you can bend your legs and lower your trunk.

c) How much discomfort you feel at the legs and knees.

d) How much discomfort you feel at the legs and knees.

The above factors are interrelated, so that, in experimenting with each rear foot angle, you may have to make a comprise on the way you retreat your trunk to suit yourself. After you have experimented with a given posture, you repeat the whole experiment with another posture.

Experience shows that, in general, the larger is the rear foot angle in relation to the direction of the front foot, and the wider is the lateral distance between the two heels, the easier you can shift your trunk over rear leg and can bend down lower. With a 30-degree rear foot angle, the leeway for your retreating and bending down is very limited. On the other hand, if your rear foot angle is 100 degrees, toes partly pointing rearward, you can creep down very low to assume the "Single Whip low form," (or "Serpent Creeps Down"), with a perpendicular trunk directly over the retreated rear leg. For general purpose, Yang Chengfu used a rear foot angle about 80 degrees sidewise in most cases.

(4) A case of 30-degree Rear Foot Angle

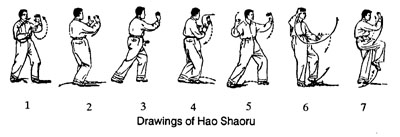

For comparison, a 30-degree rear foot angle with a perpendicular

trunk has been mentioned in section (2)-C and Section (3). This

is exactly the body alignment of the Hao style. It may be of interest

to have a look at some of the drawings of Hao Shaoru (1908-1983),

the third generation heir of this style. While the fourth picture

is "Play the Guitar," the fifth, sixth and seventh drawings

are respectively "Single Whip," "Single Whip Low

Form," and "Golden Cock Stands on One Leg." While

not bending very low or retreating the trunk for the whole series,

their Taijiquan is not weak. Rather, they apply very sophisticated

internal energy in every movement. This strength can be sensed

from the drawings by any experienced practitioner. With different

principles and different strength applications, their forms should

not be mingled with those of the Yang style, continued solo exercise.

Of course, for self-defense, you can apply the method or strength

of any style of Taijiquan.